Citation

Leavy, B. (2008), "Prahalads new value creation formula: N=1, R=G", Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 36 No. 6. https://doi.org/10.1108/sl.2008.26136fae.001

Publisher

:Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2008, Emerald Group Publishing Limited

Prahalads new value creation formula: N=1, R=G

Article Type: The strategist’s bookshelf From: Strategy & Leadership, Volume 36, Issue 6

Prahalad’s new value creation formula: N=1, R=G

Brian Leavy

Brian Leavy is AIB Professor of Strategic Management at Dublin City University Business School (brian.leavy@dcu.ie) and a Strategy & Leadership contributing editor.

The New Age of Innovation: Driving Co-created Value through Global Networks

C.K. Prahalad and M.S. Krishnan, McGraw-Hill, 2008, 257 pp.

“Increasingly, successful companies do not just add value, they reinvent it. Their focus of strategic analysis is not the company or even the industry but the value-creating system itself, within which different economic actors – suppliers, business partners, allies, customers – work together to co-produce value. Their key strategic task is the reconfiguration of roles and relationships among this constellation of actors, in order to mobilize the creation of value in new forms and by new players. And their underlying strategic goal is to create an ever-improving fit between competencies and customers. To put it another way, successful companies conceive of strategy as systematic social innovation: the continuous design and redesign of complex business systems.” – Richard Normann and Rafael Ramirez, Harvard Business Review, 1993[1]

This early glimpse of the evolving nature of the value-creation process, offered by noted theorists Richard Normann and Rafael Ramirez over fifteen years ago, was remarkably prescient. In the following years, few have done more to develop models for operating in the new competitive landscape than world renowned strategist C.K. Prahalad (acclaimed by the London Times as “the #1 most influential management thinker in the world”). His latest must-read book is The New Age of Innovation: Driving Co-created Value through Global Networks (co-authored with M.S. Krishnan, a colleague at the University of Michigan).

The New Age of Innovation seeks to build on foundations already laid down by Prahalad in The Future of Competition (with V.K. Ramaswamy[2]) and The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid. These earlier books can be seen to have presented “a unified message” which “touched on three critical aspects of innovation and value creation,” that “value will increasingly be co-created with consumers,” in both the richer and poorer parts of the world, that “no single firm has the knowledge, skills and resources it needs to co-create value with consumers,” and that “the emerging markets can be a source of innovation.” In taking this research further, the authors became struck by a fourth development, the “rapid acceleration in outsourcing of information-related work.” These four insights have led them to offer in this latest book a “new and unique perspective on the essence of innovation,” with a particular emphasis on the “critical operational link” – the business processes and analytics that “mediate between innovations, business models, and day-to-day operations.” Prahalad and Krishnan focus on how to build “organizational capabilities that allow a firm to create the capacity for continuous innovation.”

We now operate in an N=1, Resources=Global world

The opportunity for new growth and continuous innovation over the coming decade lies in the transformation already underway in the wider business environment. “We have finally reached the point where the confluence of connectivity, digitization, and the convergence of industry and technology boundaries are creating a new dynamic between consumers and firms.” The authors characterize the new value creation landscape as an N=1, R=G world, where N=1 represents the goal of creating a highly personalized experience for each consumer, one consumer at a time, while R=G (Resources = Global) reflects the need to be able to access the resources needed to do that from anywhere in the world. Increasingly, companies will have to learn how to mobilize the “resources of many” to “satisfy the needs of one,” and this book aims to help them in that endeavor. The first half of The New Age of Innovation deals primarily with the “what” and “why” of the nature of the transformation towards an N=1, R=G world, and the second half sets out to help firms to determine how they can systematically migrate from where they are to where they want to get to.

Many of the main conceptual underpinnings needed in understanding what is different about an N=1, R=G competitive landscape and what is needed to be successful within it were already laid out in The Future of Competition, so The New Age of Innovation opens with a review of the fundamental change currently taking place across the industrial landscape which is “set to alter the very nature of the firm and how it creates value.” As Prahalad and Krishnan set out to demonstrate, this transformation is already well advanced in a number of quite diverse sectors, and few industries are likely to remain unaffected by it.

Most businesses today are still variants on “the model that started the industrial revolution,” one based on the premise that consumers were undifferentiated and that resource ownership was the primary route to value capture for the firm. This was idea behind Henry Ford’s Model T. A feature of most traditional value chain configurations is that they had to force compromises onto the majority of consumers (as George Stalk and his colleagues at the Boston Consulting Group pointed out many years ago[3]), because they were unable to deliver high levels of personalization at prices that most could afford. The model implicit in N=1, R=G is “180 degrees different,” and looks capable of releasing an enormous reservoir of trapped value by breaking as many of these compromises as possible right across the commercial spectrum. Many companies are already well on their way to being pioneers in this new approach.

A lesson for established industries and new agers

Not surprisingly, new age companies like Amazon, Apple and Google feature prominently among their number. However, the authors also provide us with convincing examples from more traditional sectors, including high-school tutoring (TutorVista), truck tires (Goodyear), footwear (Pomarfin) and health insurance (ICICI Prudential). How is N=1 shaping up in the tire industry? Can this really be transformed into a high-tech, high-touch business? The traditional business model in the tire industry is that manufacturers typically sold tires to the truck makers on an OEM basis, hoping that drivers would also chose the same brand when the time came for replacement. Today, firms like Goodyear are already experimenting with business models that offer their tires as part of a cost-per-mile service package rather than as discrete products, with revenue based on tire usage, not on a one-time tire sale. The pricing is individualized, based on a range of factors specific to the particular customer, including types of load (heavy or light), typical route structures (city or highway), and characteristics of the fleet owners such as driver training, maintenance of correct tire pressures, tire rotation frequency and other factors relevant to rate of wear. The interaction with the customer shifts from being transaction-based to relationship-oriented. The tire still lies at the core of the business, but data take on a major role in the value-creation process. The new model requires ongoing and continuous measurement of usage and the factors that contribute to it, including driver skill and behavior, the value of which can be further enhanced with the installation of sensors able to measure tire usage on a real-time basis and relay the information to a central data center for analysis. The company can then add even further value in the form of training and expert advice. Of course, to get driver buy-in to this more intrusive and transparent arrangement, the incentive structure must also be modified to reward and promote the desired behaviors.

When viewed in this way, is the tire business any longer a commodity business or is it “a highly differentiated, service-oriented business that co-creates a unique driving experience for a specific driver” while improving their driving skills as well? As Prahalad and Krishnan point out, there are three distinct transformations taking place in this example, (1) the firm is moving from selling a product to selling a service; (2) the firm is moving from a transactional relationship with a customer to a service relationship with a customer, and (3) a traditional B2B business takes on more of a B2C character. As the authors explain, “In the new competitive arena of one customer at a time and global networks of resources, B2B and B2C definitions converge.”

The examples of TutorVista, Pomarfin and ICICI Prudential are equally insightful and compelling. TutorVista is still a relatively young organization currently in the process of transforming the traditional business model in high school tutoring to one that offers students the flexibility to study what they want, where they want, when they want (tutors are recruited across multiple time zones, and tuition is delivered online), at their chosen pace and intensity, and with their own choice of tutor, and it has secured the custom of over 10,000 paying students and access to the talent of over 600 tutors globally. Pomarfin is a small Finnish family-owner concern which is pioneering the development of a business model that will allow customers to buy shoes that are made to their precise foot measurements and in a style and shape of their own choosing, using digital scanning technology at store level and drawing on the diverse resources and skills of Italian designers, Estonian manufacturers and Finnish software developers to configure a business ecosystem capable of delivering this proposition to its customers at very competitive prices. ICICI Prudential, a joint venture between Prudential plc and leading Indian bank, ICICI, is creating new value in the provision of health insurance for diabetics, an area that many players in the insurance industry have tended to back away from because of the higher risks that diabetics run of succumbing to heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, adult blindness and amputations, and the sensitivity of the risk level to life style factors. A key feature of the ICICI Prudential offering is a range of incentives designed to encourage its customers to become involved in the day-to-day management of their own condition with the help of an individually designed wellness program and through partnerships with leading healthcare providers. The value of the proposition here also, will eventually be enhanced with the introduction of sensor technology and remote diagnostics.

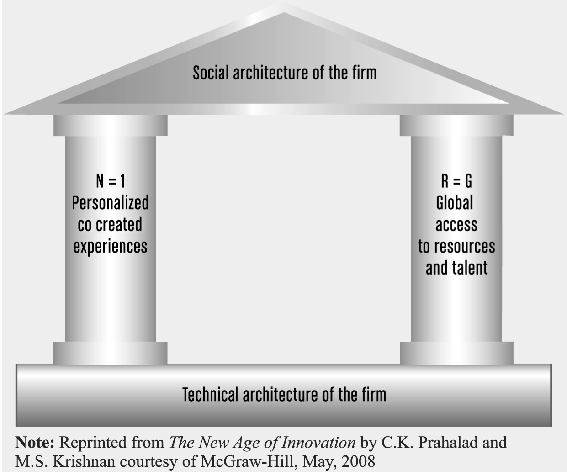

Having demonstrated that the transformation to N=1, R=G is already becoming quite widely based, the authors then go on to examine in some detail the operational linkages that will be key to being able to compete successfully in an N=1, R=G world (see the authors’ Figure 1.1[4] (Exhibit 1)), with primary emphasis on business processes, focused analytics and technical architecture.

The operational details

In an N=1, R=G world, business processes become “the core enabler of innovative capacity in the firm,” and as digitization “increasingly permeates every aspect of business,” a firm’s ICT architecture becomes a major enabler (or disabler) of process flexibility. And process flexibility is key. An N=1, R=G world demands that companies be able to foster innovation and efficiency simultaneously through business processes that are capable of offering high degrees of variation and individuality at the customer interface, while also trying to maintain a discipline of zero-variance closer to the operating core. To understand this more clearly, let’s return briefly to the Goodyear example. Even as the company has been transforming its business model into one capable of offering a highly personalized cost-per-mile service, while constantly experimenting with ways to make the customer experience even more individualized, it must also continue to manufacture tires to six sigma levels of quality, consistency, reliability and efficiency. Likewise, in the case of Pomarfin, the design and fit of the shoes may be highly personalized, yet the shoes must still be manufactured to very tight standards of process control and consistency, in order to be profitable at prices that can command mass market appeal. “N=1 pioneers” are therefore “creating new benchmarks for leveraging business processes.”

It is clear from the examples highlighted that information is playing a crucial role in the transformation of traditional mass-produced products and services into highly individualized customer experiences. Knowledge-intensity is pervasive in the world of N=1, R=G, and “the new competitive landscape requires continuous analysis of data for insight.” The key to this competitive capability is sophisticated, focused, analytics. Ongoing developments in the “digitization of business processes, the Internet, and evolving ICT architecture” enable a level of “real-time predictive modeling” unavailable to most firms up to now, and, accordingly to the authors, these analytical capabilities lie “at the heart of effective management in an N=1, R=G world.” “The transformation to a customer-centric co-creation view of value pushes firms to new frontiers on the price-performance envelope, “and ever-improving, ever more focused, industry-leading, proprietary analytics are playing a key role in this process.

Key analytics

To begin with, the right analytics are key to supply chain visibility, which makes them crucial to the effective management of the R=G dimension. This can be readily illustrated by looking at the leading-edge practices of some of the best known exemplars of effective global supply chain management today, companies like Li & Fung, Schneider Electric, UPS, and FedEx. At the heart of an operation like Li & Fung, lies a set of analytics that gives the company visibility to all of the variables that can influence its ability to orchestrate the supply of a consignment of a garment of any particular size, color and design from “plant A in Thailand to serve JCPenney in Dallas,” at the right price and on time. Just as important is level of “granularity” provided by the analytics to ensure the most appropriate performance metrics and resource requirements are being applied at every business process step along the way. “Visibility to processes and data within global supply chains (R=G) is crucial for building the multiple layers of capabilities that are critical for the dynamic reconfiguration of resources.”

In the case of UPS, the authors also track its steady evolution on the N=1 dimension and link this to its ever-improving analytics. Years ago, customers would have had to deliver their parcels to a central collection centre and wait for several days for acknowledgement of delivery. Today, the company is developing the capabilities that will allow it to pick up packages at each customer’s site and at a time of the customer’s choosing. Customers also now have easy-to-access visibility into where their packages are in the UPS system at any given time. This is “a significant transformation from a business process focus on the firm to a business process focus on the each unique customer experience” and “careful attention to business processes, integration of analytics and capacity to dynamically reconfigure resources is behind this transformation.” A core element of this development is UPS’s new “routing analytics engine” that can analyze “package delivery, weather and traffic data to route each truck” even to the point of “minimizing left turns so that trucks are not held up at traffic junctions,” an overall improvement in process that has “saved the UPS fleet 1.9 million miles of travel per year,” even while increasing the level of personalization on offer to customers.

As business process analytics becomes more and more a highly specialized domain, not many firms will be able to meet all of their needs in-house. Increasingly they won’t have to. The strategic partnership between the US-based hospitality company Wyndham Worldwide, and Marketics, a “novel marketing analytics company” based in Bangalore, is just one of a number of examples examined by the authors of The New Age of Innovation to highlight this development.

A system in continuous flux

It is not too hard to see from all of this the quality and appropriateness of any firm’s underlying ICT architecture will be a key success requirement in this new competitive landscape. The “entire network – consumers, the firm, and its collaborating suppliers” cannot be viewed as a static system but as “a system in continuous flux,” because the “ability of individual consumers to shape their experiences via access to a flexible and responsive global system is at the heart of value creation” in an N=1, R=G world. Some of the new demands that will be placed on the underlying ICT architecture will include the “capacity to link large systems and multiple databases,” the ability to manage the tension between “proprietary systems and transparency,” and the ability the balance the inevitable increase in ICT system complexity and sophistication with the concomitant need for ease of access and user-friendliness. The authors offer a diagnostic framework for assessing how far along the journey to N=1, R=G your ICT architecture is at any stage along the way, and examine in some detail the four minimum requirements for getting there in this important area: (1) a component-based design of business processes; (2) ubiquitous accessibility through corporate intranet and the Internet; (3) open interfaces to data and external systems and (4) an integrated capability for analytics.

Disrupting the company mindset

For Prahalad and Krishnan, the transformation to N=1, R=G is more than a just a technological phenomenon. It is primarily “a social movement,” which will affect not only the way that firms and consumers will relate to each other in the future, but will also alter radically the nature of the firm and how its technical and social systems interplay. The “social architecture” of the firm is “the sum of the systems, processes, beliefs, and values that determine an individual’s behaviors, perspectives and skills in an organization.” Over time, such customary ways of operating collectively lead to “a predictable way of thinking about opportunities, competitiveness, consumers and performance,” that the authors refer to as the “dominant logic of the firm” (drawing on a powerful concept introduced to the strategy literature by C.K. Prahalad and Richard Bettis in the mid-1980s[5]). So the journey to N=1, R=G will also involve a significant change in company mindset and culture, and technical change alone will not bring this about. “The reasons why business process transformation initiatives do not bear fruit in many organizations are largely managerial and social.”

While the full transformation to an N=1, R=G operation will be a radical one for most companies, the authors believe that the journey need not be too disruptive. “There is enough organizational evidence that shows that continuous experimentation and learning followed by consolidation can lead to major new capabilities in a short period of 3 to 5 years without major organizational trauma,” and they illustrate this with a detailed examination of a recent transformation at Madras Cement, a change process that was driven by the conviction of the company leaders that “business performance would be dramatically improved by streamlining social and technical processes.”

The speed of evolution

The authors end their book with a useful summary of their central arguments and ideas, and by reminding us why this trend is happening “faster than anyone expected.” By 2015 to 2020, it will no longer be “big news.” Why? Growing interconnectivity worldwide (5 billion people worldwide will be interconnected through mobile and Internet communications), the rapid evolution of social network platforms and technologies, widening access to infrastructure, and the ongoing development of ever more powerful analytics and data based management capabilities are all driving change in this direction. Most important of all is the generation of 12 to 15 years old today who are “growing up in a new environment in which they are used to individuality and self-expression” and are set to be among the most active consumers within a decade. The authors end by offering some guidance to senior managers about how to get their journey to N=1, R=G underway. “The only certainty is N=1, R=G, not the manifestations of this core reality.” The journey starts with the need to develop a clear point of view about the future and a vision for what N=1, R=G will mean for their organization, because migration paths are likely to be different for different firms and different industries. So it is “prudent to take small measured steps by building specific milestones” which will “allow an organization to evolve rapidly,” with each one of these milestones “carefully designed to build new capabilities in the organization.” The key message to managers is that they should “fold the future in” rather than try to extrapolate from current positions and practices, because N=1, R=G will be a very different business environment.

The New Age of Innovation is brimming with ideas and insights, and while it is not the easiest book to read, it is an important one that will repay the effort. For those who stay the course, this book will help them gain a clearer picture of the contours defining the emerging N=1, R=G competitive landscape, while offering them deeper insight into its main organizational and managerial implications.

C.K. Prahalad is the Paul and Ruth McCracken Distinguished University Professor of Strategy at the Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, where his colleague and co-author on this latest book, M.S. Krishnan, is a Michael R. and Mary Kay Hallman Fellow and professor of business information technology.

Notes

1. Normann, R. and Ramirez, R., “From value chain to value constellation: designing interactive strategy,” Harvard Business Review, July-August, 1993, pp. 65-77.

2. Ramaswamy, Venkat, “Co-creating value through customers’ experiences: the Nike case,” Strategy & Leadership, Vol. 36, No. 5, September/October 2008.

3. Stalk, G., Pecaut, D.K. and Burnett, B., “Breaking compromises, breakaway growth”, Harvard Business Review, September-October, 1996, pp. 131-9.

4. Figure 1.1 entitled “The New House of Innovation” in The New Age of Innovation: Driving Co-created Value Through Global Networks, C.K. Prahalad and M.S. Krishnan, McGraw-Hill, 2008, reprinted by permission of the publisher.

5. Prahalad, C.K. and Bettis, R.A. (1986), “The dominant logic: a new link between diversity and performance”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 7 No. 6, pp. 485-501.